Kayan, Sihan, and Lahanan: Three Tribes from North Sarawak, Malaysia, Borneo

The three tribes are collectively known as Orang Ulu (People of the Interior), and most of their members are heavily tattooed. Unlike the Iban people, the Orang Ulu tattooists were exclusively women. The Orang Ulu did not use specific models for long, but the surviving patterns remain incredible due to their abstract simplicity. Their tattooing equipment was made from natural materials such as wood, grass stalks, and pigments extracted from jungle plants, collected from a place where every living and inanimate thing has its own soul. Until recently, tattooing was not categorized as an art form.

KAYAN

In the 1900s, the process of a girl receiving a tattoo within the Kayan tribe was an extremely serious undertaking, not only due to the terrible pain but also because of the ceremonial significance, which was considered an honour for the tattooed individual. The process could sometimes last up to four years, as only small areas of skin were tattooed at a time, with long breaks between sessions. For example, a ten-year-old girl would first have her toes and feet tattooed, followed by her forearms, but only after a year’s hiatus. The following year, the thighs were next. These tattoos were believed to protect them from evil spirits.

There was also a universal tattoo that every woman received, called “tedek-tuh’duck.” It was believed that these tattoos illuminated the afterlife like torches, guiding them to their ancestors. Women were always the foremost experts in this art, while men merely carved the models into pieces of wood. The position of the tattooist in this society was very high on the social ladder, recognized on par with scribes and blacksmiths.

Most female tattooists from the Kayan tribe were bound by social taboos. For example, if a female tattooist had a newborn baby, she was forbidden from tattooing because it was believed that the bloodshed would attract evil spirits, which would then possess the children or cause illness and death. They could not tattoo during the rice planting season, nor could they do so if there was a new person in the “house of spirits,” as this would anger the spirits. If they had nightmares (of floods, bloodshed) during the tattooing phase, they stopped the process.

During the tattooing processes, the female tattooists could not eat raw meat or fish, arguing that spirits would possess them. If they broke these rules, the tattoos would no longer shine brightly enough in the afterlife and would lead them to death. Often, these women chose this profession because they believed that the spirit of tattooists, “Bua Kalunk,” protected them from illnesses.

The tattooing tools were simple, consisting of a pair of thorn points (ulang), a small wooden mallet (tukun or pepak), which were kept in a small wooden box (bungan). The main tool was a stick with a prominent tip, to the end of which three or four tiny needles were attached. The mallet was made of strong wood, and its handle was wrapped with a piece of rope. The ink was a mixture of soot, water, and sugarcane extract, kept in a small wooden box called “uit-ulang.” It was believed that the best soot came from the burned bottom of a pot, but soot from burned resin was also used.

The designs were carved into a piece of wood (kelinge), then dipped in ink, and then pressed onto the area of skin where the tattoo was planned, thus creating the design they would work from. The person awaiting the tattoo lay on the floor, while the tattooist and her assistant positioned themselves on either side of the client. First, the female tattooist dipped a palm leaf into the “ink” and then pressed it onto the area to be tattooed, creating the design on the person’s skin. Along the straight lines, the tattooist stitched the outline (ikor), and then between the lines, she pressed a carved piece of wood dipped in “ink” onto the skin. The tattooist or her assistant stretched the skin where the tattoo was to be applied with their feet. Then, she dipped the needle attached to the stick into the ink and tapped it with the small wooden mallet, thus injecting the pigment under the skin (along the contour lines). The process was very painful, but the tattooist was never moved, continuing the tattooing throughout.

It was said that the price of tattoos was usually a fixed amount. Tattoos on the forearms ranged between 8 and 20 dollars, while for the thighs, it rose to 60 dollars if a very refined job was requested. The payment for tattooing the fingers was a small sword. In 2002, a Kayan woman recounted that the payment for the tattoos on her thigh was 20 dollars and two pigs. In the 19th century, it was rumoured that if a tattooist asked for too much money for the work, she would lose her life within a year.

SIHAN and LAHANAN

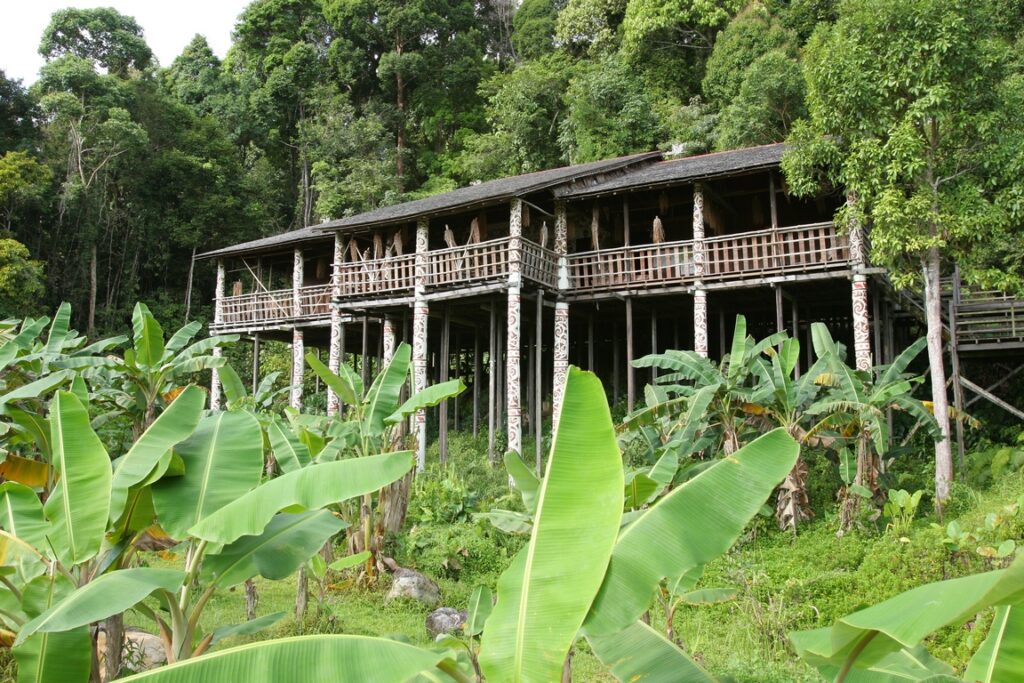

Sihan is a native tribe consisting of about 150 people living in a “longhouse,” two hours from the Rajang River. They speak a Kayan dialect, and their tattooing style is very similar to that of the Kayan. The Sihan maintained their tattooing tradition longer than the Kayan. The Kayan stopped traditional tattooing 50 years ago, while the Sihan only stopped 30 years ago.

A 50-year-old Sihan woman, Konok, recounted that she received her first tattoo on her arm before marriage, which was mandatory before the wedding. According to her, no man would marry a woman without a tattoo. Here, too, women were the tattoo artists, and they worked with the same methods as the Kayan. The social position of the female tattooists was very high within the tribe and was inherited from mother to daughter. After their death, they were buried with their equipment.

Lahanan was a slightly larger tribe neighboring Sihan, which was also famous for the art of tattooing, where women also tattooed, and the art was inherited maternally.

A 60-year-old woman, Bangu, recounted her experiences from 1950: “Several women held me down, each holding one of my hands and legs. Then one of them stretched my skin, but the tattooist did not start the work until I calmed down. I had to go through this because otherwise, I couldn’t have gotten married. One arm took four hours, the other four hours. One leg took four days, the other four days. I was 15 then, but I had all my tattoos done by the age of 16. In other cases, it would have taken longer, but I was eager to get married.”

An 85-year-old man recounted that he got his first tattoo at the age of 15, after which a celebration was held in his honour, as it was a rite of passage to manhood. Lahanan men who did not yet have tattoos were ashamed of their tattooed peers, as it was believed that only true warriors knew the pain of a real tattoo.

Forgotten Traditions

Today, the traditional art of tattooing is dying out among the Orang Ulu tribes. The interruption of this tradition is due to missionaries and continuous modernization. The Orang Ulu are no longer as interested in the traditional art of tattooing; they are more attracted to the cities where they take on suburban jobs, meanwhile getting acquainted with other cultures, including the art of modern tattooing, which is less painful, and the models have also changed, with dragons, eagles, etc., being the most popular nowadays.

Missionaries continue to convert people to abandon their old traditions and cultures, and they are trying to convince the Malaysian government to build the largest hydroelectric power plant in Southeast Asia in the area that was their home. Due to the construction, thousands of indigenous people have already been displaced from their lands, where they have lived for centuries. Finally, the artificial lake will flood a part of the rainforest, which was home to many endangered animals. The Orang Ulu have not yet succumbed to modernization, but as the rainforest disappears, the traditional art of tattooing is slowly fading into oblivion.