Among the Bantu and Makonde-speaking tribes, tattoos have always been more complex compared to the tattoos of other indigenous Mozambican tribes, and this remains true today. The resonance of the tattooing tradition is due, to some extent, to the area occupied by the Makonde tribe, a place characterized by high plateaus that prevented European contact, even with Western Europe, until the early 20th century. At the same time, Makonde cosmology and myths still glorify the great deeds, knowledge, and superior attributes of their esteemed ancestors, especially the tattooed women who became deities after their death.

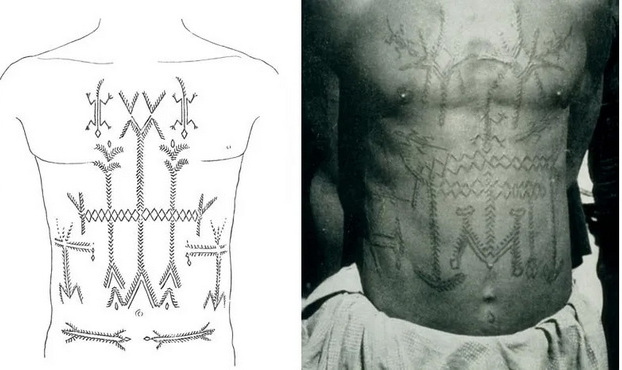

Traditionally, Makonde tattoos were considered regional indicators or signs, so each tribe chose unique motifs that were drawn in various ways. The face and other body parts featured cords, angles, and straight or zigzag lines, sometimes supplemented with a circle, a rhombus, a dot, or an animal motif. These motifs have largely remained unchanged to this day, as tattooists from every Makonde generation only applied minor variations to the tattooing motifs, thinking in line with the basic principles of tradition. Currently, the only significant innovation in the tattooing tradition is the technology itself, where the old triangular knife has been replaced by a razor blade model that cuts the skin more evenly and precisely.

Tattoo Motifs

Common motifs such as the spider (lidangadanga), crocodile (nantchiwanuwe), and even cassava roots (nkana) were often associated with magic. To this day, Makonde women believe in the supernatural power of tattoos drawn on their stomachs (mankani) and the inner side of their thighs (nchika), which helps them acquire a husband. Furthermore, the motifs decorating these body parts – typically palm trees or their fruits (nadi) and especially lizards (magwanula) – were believed to have a positive effect on fertility.

At the same time, according to Makonde tattooing custom, tattoos around the navel and pubic area may be related to an ancient pre-magical tradition aimed at preventing the penetration or possession by evil forces of those human body parts that are more vulnerable (e.g., the natural orifices of the body).

Armitage (1924) cites several cases of cupping (scarification, cutting) on the navel of Bantu-speaking women of the Gonja and Dagomba to prevent illness, and in 1995, anthropologists Nevadomsky and Aisien presented five types of tattoos starting from the navel – the center of life – on Bini women from Benin. Not surprisingly, members of the Bini tribe made the dye for the tattoos from leaves and charcoal, and at funerals, grieving women and men would draw a line of charcoal on their foreheads to scare away the deceased, who might try to drag family members after them to the land of the dead.

The Spiritual Life of the Makonde Tribe

The Makonde tribe believed in a cosmology ruled by an independent, impersonal force (ntela), the appeasement of ancestral spirits (mahoka), which could be good or evil, and a concept of all-pervasive spirituality (nnandenga) and sorcerers who represented the forces of evil. They often turned to the spirits of their ancestors to heal illnesses or bring success in hunting and harvesting. The $Mahoka$, like the $Nnugu$ – a powerful god to whom the Makonde tribe prayed for rain.

However, the spirits of the dead, called mapiko, only haunted women and the uninitiated, while sorcerers created invisible servants from people (lindandosa) and sent them to the fields where they could practice black magic.

A constant fear of death defined the Makonde belief, and the signs of this fear had to be contained, as death posed a threat to the fundamental cosmic assumptions upon which their entire society was based. Every woman understood that their presence and participation in society could lead to the intervention of evil spiritual forces appearing in the form of mahoka, nnandenga, lindandosa, or maqiko, as they were the ones who guaranteed social, physical, and economic survival. From this perspective, the art of tattooing among the Makonde was an important tool for genuine connection between human beings and the spirits: it is quite clear that the motifs tattooed on women helped them demonstrate their commitment to the life-giving force and the initiatory socialization process. At the same time, the tattoos formed a pictorial language through which these relationships were tangibly expressed and mediated to provide the wearer with the means to control the world around them. Similarly, Makonde sculptures, as well as other more utilitarian objects like water bowls, embodied female and reproductive attributes, reinforcing the commitment to order and stability, and were often adorned with tattooing motifs. Just like some ancient tools used for transporting water, beer, honey, and seeds, these objects were considered female symbols due to their excellence. They served as a channel for the symbolic meanings of the tattoos on Makonde women’s bodies, which connected the human community with the spirits and ancestors of the Makonde tribes of Mozambique.